A man does not plant a tree for himself, he plants it for posterity – Alexander Smith (Scottish Poet, 1830-1867)

Several of my friends told me that I was too old to start an orchard. According to a Chinese proverb: The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The second best time is now. I marvel at what I have planted, watching as it grows, coming to life each spring and changing through the seasons. So in the spring of 2018, I finally planted my orchard, seventeen fruit trees plus three American chestnuts. This will be part of my legacy. The fruit and nuts that they eventually will bear during my lifetime will be icing on the cake.

Fifteen years ago when I bought these 37 acres, half of which are wooded, I drew up a plan for my orchard. The odds of my being a successful orchardist may have increased over this ten year period, as I learned the importance of creating an environment that replicates the complex soil food web that exists in the forest floor.

I read three of Michael Phillips’ books: The Apple Grower – A Guide for the Organic Orchardist; The Holistic Orchard – Tree Fruits and Berries the Biological Way and Mycorrhizal Planet – How Symbiotic Fungi Work with Roots to Support Plant Health and Build Soil Fertility.

A tree that falls in the woods has a rich afterlife. As it rots, it becomes a habitat for a diverse array of organisms, eventually teeming with life from microbes to mushrooms and becoming a nursery for new seedlings. The dead trees enrich the soil with nutrients and hold volumes of water that sustain the life of the forest.

Michael Phillips explains the importance of fostering the mycorrhizal fungal life of the soil that will bring nutrients to the roots of fruit trees. This happens naturally in woodlands where there is a symbiotic relationship between the tree roots that feed sugar, produced through photosynthesis, to the microbes and fungal life in the soil which in turn break down minerals in the soil and transport them via a vast network of mycelia to the tree roots.

rhi·zo·sphere /ˈrīzəˌsfir/ noun ECOLOGY – The region of soil in the vicinity of plant roots in which the chemistry and microbiology is influenced by their growth, respiration and nutrient exchange.

So, as I have begun to understand the importance of the soil food web in fostering a healthy organic orchard, I chased after tree service companies in the area, asking them to dump their wood chips on my land. After Superstorm Sandy, the power company cut down scores of trees to protect and repair its electric lines. That provided a six-year old hill of aged wood chips that I retrieved from the property of my neighbor Socrates Lambrinides. Thus, I went about trying to recreate conditions similar to the rich forest floor that spawns countless miles of mycelia that comprise much of the rhizosphere.

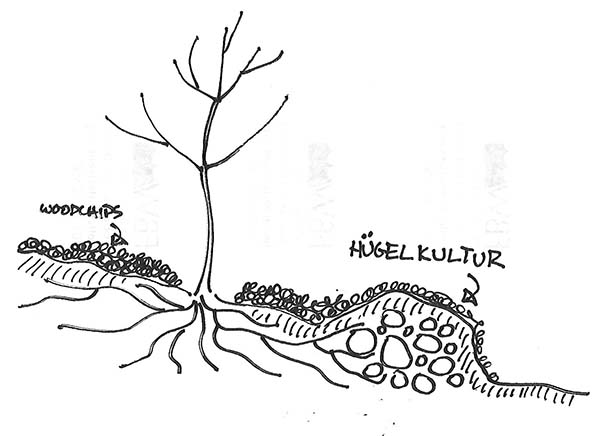

The previous fall, my helper Mike Powell and I dug trenches in an arc, about six to eight feet across and a foot deep, downhill from where each fruit tree would be planted. We filled each trench with logs, some fresh, some rotting; branches; wood chips and compost. Then the soil from the trenches was mounded over the top. This is called Hügelkultur, a horticulture technique employed for hundreds of years in Germany and Eastern Europe and more recently revived in permaculture practice. As mentioned above, the buried wood and organic material absorb and retain moisture, release nutrients as they break down and support fungal activity in the soil.

After planting the trees in the spring, Mike and I began to fill up my pickup with wood chips and make countless trips to the the orchard. I marked off a ten by ten foot square around each tree adding the required soil amendments based on my latest soil test and layers of cardboard, compost, hay, leaves, aged wood chips and a top layer of fresh wood chips. Where the layers are thick enough, it will kill the grass and create a springy organic blanket, similar to the forest floor.

I planted two paw paw trees, one Susquehana the other a Shenandoah; three pear trees, Summer Crisp, Nova and Seckel; a Montmorency cherry; a Meader persimmon; two plums that grow together, Purple Heart and Underwood; a Hargrand apricot; a Redhaven peach; a Dolgo crabapple and five apple trees: Williams Pride, Liberty, Golden Grimes, Goldrush and Rhode Island Greening. All of the apple trees were grafted onto an Antonovka rootstock that will produce a standard tree that I chose for its extensive root system and potential longer life. Likewise, for the other fruit trees I avoided dwarf and semi-dwarf rootstocks. Most varieties were selected for their compatibility with my region and their resistance to common diseases.

An eight foot fence surrounds the orchard to keep out the marauding deer. I planted the three American Chestnut trees and the crabapple at the top of the hill above the orchard at the edge of the woodlands to take advantage of a ready-made forest floor.

Cover crops started between wood chip plots where fruit trees were planted.

I should have begun cover crops to prepare the soil before planting the trees but alas, I never got around to it. So this fall, I laid down some paper over some of the grass areas between the wood chip-covered tree plots. I then covered the paper with compost and grass clippings, and sowed oats, field peas and tillage radish. Soon a thick bed of cover crops emerged and continued to grow until the first big snow storm hit on November 15, followed by temperatures dipping to the single digits. In the spring I will sow more cover crops. The cover crops will displace the grass and ultimately be covered with yet more wood chips.

I am also learning the value of perennial plant guilds. In the orchard, I planted hardy kiwi, American cranberries, gooseberries and seaberries. In years to come, I plan to add hazelnuts, currents and lingonberries. To attract pollinators, I will add yarrow, daffodils, dill, purple coneflower and the like. There will also be comfrey, transplanted from my vegetable garden, whose taproot loosens the soil and whose leaves provide a nutrient-rich mulch. The guild also must include nitrogen fixing plants such as False Blue Indigo, Siberian pea-shrub and lead plant.

So my orchard is evolving into an edible landscape or a food forest. I know, the name is misleading, for it will not look like a forest but it will be a diverse ecosystem that will produce an array of fruit, nuts and berries atop a rich organic base akin to a forest floor.

A note on the “Back to Eden” garden. You can take a tour on YouTube but take the advice with a grain of salt. Wood chips alone are unlikely to produce good results. Fresh wood chips will tie up nitrogen in the soil. Test your soil and apply amendments as needed to achieve a proper balance of nutrients. Cover crops, compost, compost teas and mulches in addition to wood chips will increase your chances of producing the right conditions in your soil. To learn more be sure to read Michael Phillips’ books.