A zillion tons of materials that could be composted get carted off to landfills each day. I manage to divert about 7 tons of this annually: spent coffee grounds from my local Starbucks in Hoboken. I gather up wagon-loads of hay cut from my fields and leaves from the wooded areas. These carbon-rich materials are mixed with the nitrogen-rich coffee grounds to concoct my special blend of java compost.

I still have The Complete Book of Composting published by Rodale Press. I read it (not all 986 pages) back in the 1970s along with my subscription to Organic Gardening and Farming Magazine. Chapter 18 is devoted to Sir Albert Howard whose work in the early 1900s gave birth to the organic movement. Thus began my persistent habit of composting,

The nitrogen content in coffee grounds is about two percent. They also contain significant amounts of potassium plus some phosphorus, magnesium and copper, all important for growing vegetables and other plants. Yes, the coffee you drink is acidic, but coffee grounds are only slightly acidic, within the ideal range for most vegetables: pH 6.5 to 6.8.

I did a soil test on my java compost last spring and the results found high levels of potassium plus a good amount of magnesium. Organic matter registered at 18 percent. Thus, as I add more compost to the garden beds, I am upping the volume of organic material that increases the capacity of the soil to hold nutrients and also to retain water.

When I first started with the farm 10 years ago, I used manure from the dairy farm up the road to make compost. Most organic farmers will use manure for making compost and farm animals are thus integral to the whole operation. The use of coffee grounds, however, helps to avoid the risk of certain pathogens.

Beyond that, however, coffee grounds have antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. According to Linda Chalker-Scott, Ph.D: “As they decompose, coffee grounds appear to suppress some common fungal rots and wilts, including Fusarium, Pythium, and Sclerotinia species.”* So, could this be the solution to my persistent problem with early blight on my tomato plants each year?

Dr. Chalker-Scott also writes: “Humic substances, which are important chemical and structural soil components, are produced through coffee ground degradation.” Some years back, when I took a workshop at the Rodale Institute in Emmaus, Pennsylvania, they provided a session on composting. There were three items added to their compost heaps: clay, gypsum and humates.

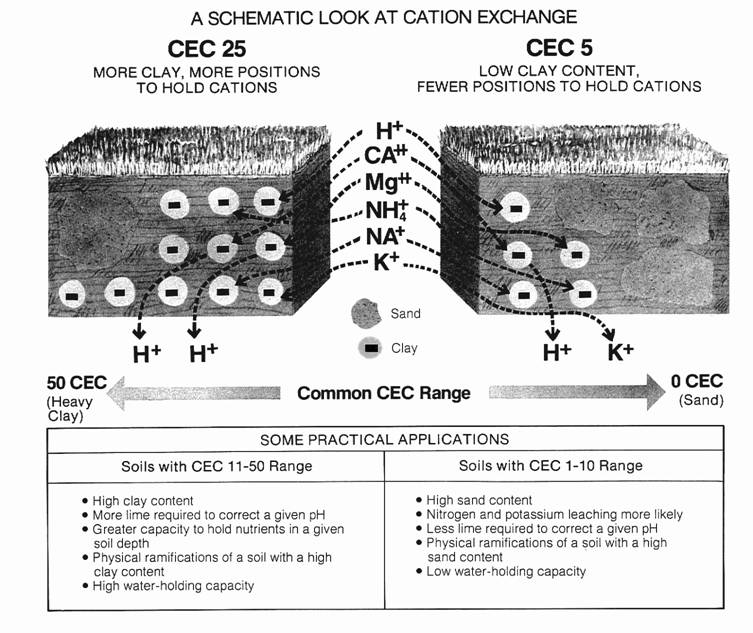

It is the negatively charged molecules of clay that allows them to bind with positively charged nutrients, mainly calcium, potassium, sodium and magnesium, preventing them from washing away, making more nutrients available to plants. So, I add clay, a relatively cheap material, to the compost piles as I turn them over. The gypsum adds calcium and sulfur to the mix but I stopped using it when my soil tests indicated that calcium exceeded the recommended levels. My supply of humates has run out, but perhaps the composted coffee grounds is supplying that element.

Currently, I have three compost heaps in various stages of decomposition. When I start a new pile, it quickly heats up. Trials** at Oregon State University found that when coffee grounds made up 25 percent of the volume of compost, temperatures ranged from 135 to 155 degrees for at least two weeks. This provided enough time to kill a significant portion of the pathogens and weed seeds. In contrast, the manure in the trials didn’t sustain these same temperatures for that long.

One winter I was able to keep one of my compost heaps hot throughout the season, turning over the steaming pile regularly, despite temperatures dipping at times below zero Fahrenheit. The extra heat has also required me to add more water, sometimes lots of it, as the compost needs to be kept moist.

Twice a week I show up at Starbucks on Washington Street in Hoboken. I provide them with about a dozen clean four gallon containers with lids. When I head up to the farm on Thursday night or Friday morning they are all full. This puts me on a weekly routine of stockpiling coffee grounds, making compost and turning over the piles. Normally, I add compost to the garden beds prior to starting new crops in the spring and again in the summer or fall when beds are reseeded with a cover crop.

I no longer dig compost into the soil. Instead I spread a thin layer on top of the soil and spread a leaf or grass mulch over the top to keep prevent the compost from drying out. The idea is to use the compost to inoculate the soil with microbes as well as provide organic matter and additional nutrients. All of my compost heaps are at the edge of a forest, the floor of which contains the greatest abundance of microbial and fungal life.

I would like to personally thank the staff of Starbucks at 314 Washington Street in Hoboken, New Jersey. What they are doing is good for the environment, and returns a rich organic material to the earth and my garden. If this idea were to spread around the world, we would be a step closer to saving the planet.

*https://s3.wp.wsu.edu/uploads/sites/403/2015/03/coffee-grounds.pdf

**https://today.oregonstate.edu/archives/2008/jul/coffee-grounds-perk-compost-pile-nitrogen